Answer

The Roman Catholic Church portrays itself as the one legitimate heir to New Testament Christianity, and the pope as the successor to Peter, the first bishop of Rome. While those details are debatable, there is no question that Roman church history reaches back to ancient times. The apostle Paul wrote his letter to the Romans about AD 55 and addressed a church body that existed prior to his first visit there (but he made no mention of Peter, though he greeted others by name). Despite repeated persecutions by the government, a vibrant Christian community existed in Rome after apostolic times. Those early Roman Christians were just like their brethren in other parts of the world—simple followers of Jesus Christ.

Things changed drastically when the Roman Emperor Constantine professed a conversion to Christianity in AD 312. He began to make changes that ultimately led to the formation of the Roman Catholic Church. He issued the Edict of Milan in 313, which granted freedom of worship throughout the empire. When doctrinal disputes arose, Constantine presided over the first ecumenical church council at Nicaea in AD 325, even though he held no official authority in the churches. By the time of Constantine’s death, Christianity was the favored, if not the official, religion of the Roman Empire. The term Roman Catholic was defined by Emperor Theodosius on February 27, 380, in the Theodosian Code. In that document, he refers to those who hold to the “religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter” as “Roman Catholic Christians” and gives them the official sanction of the empire.

The fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of the Catholic Church are really two branches of the same story, as the power was transferred from one entity to the other. From the time of Constantine (AD 312) until the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the emperors of Rome claimed a certain amount of authority within the church, even though it was disputed by many church leaders. During those formative years, there were many disputes over authority, structure, and doctrine. The emperors sought to increase their authority by granting privileges to various bishops, resulting in disputes about primacy within the churches. At the same time, some of the bishops sought to increase their authority and prestige by accusing others of false doctrine and seeking state support of their positions. Many of those disputes resulted in very sinful behavior, which are a disgrace to the name of Christ.

Just like today, some of those who lived in the leading cities tended to exalt themselves above their contemporaries in the rural areas. The third century saw the rise of an ecclesiastical hierarchy patterned after the Roman government. The bishop of a city was over the presbyters, or priests, of the local congregations, controlling the ministry of the churches, and the Bishop of Rome began to establish himself as supreme over all. Though some historians tell these details as the history of “the church,” there were many church leaders in those days who neither stooped to those levels nor acknowledged any ecclesiastical hierarchy. The vast majority of churches in the first four centuries derived their authority and doctrine from the Bible and traced their lineage directly back to the apostles, not to the church of Rome. In the New Testament, the terms elder, pastor, and bishop are used interchangeably for the spiritual leaders of any church (see 1 Peter 5:1–3 where the Greek root words are translated “elders,” “feed,” and “oversight”). By the time Gregory became pope in AD 590, the empire was in shambles, and he assumed imperial powers along with his ecclesiastical authority. From that time on, the church and state were fully intertwined as the Holy Roman Empire, with the pope exercising authority over kings and emperors.

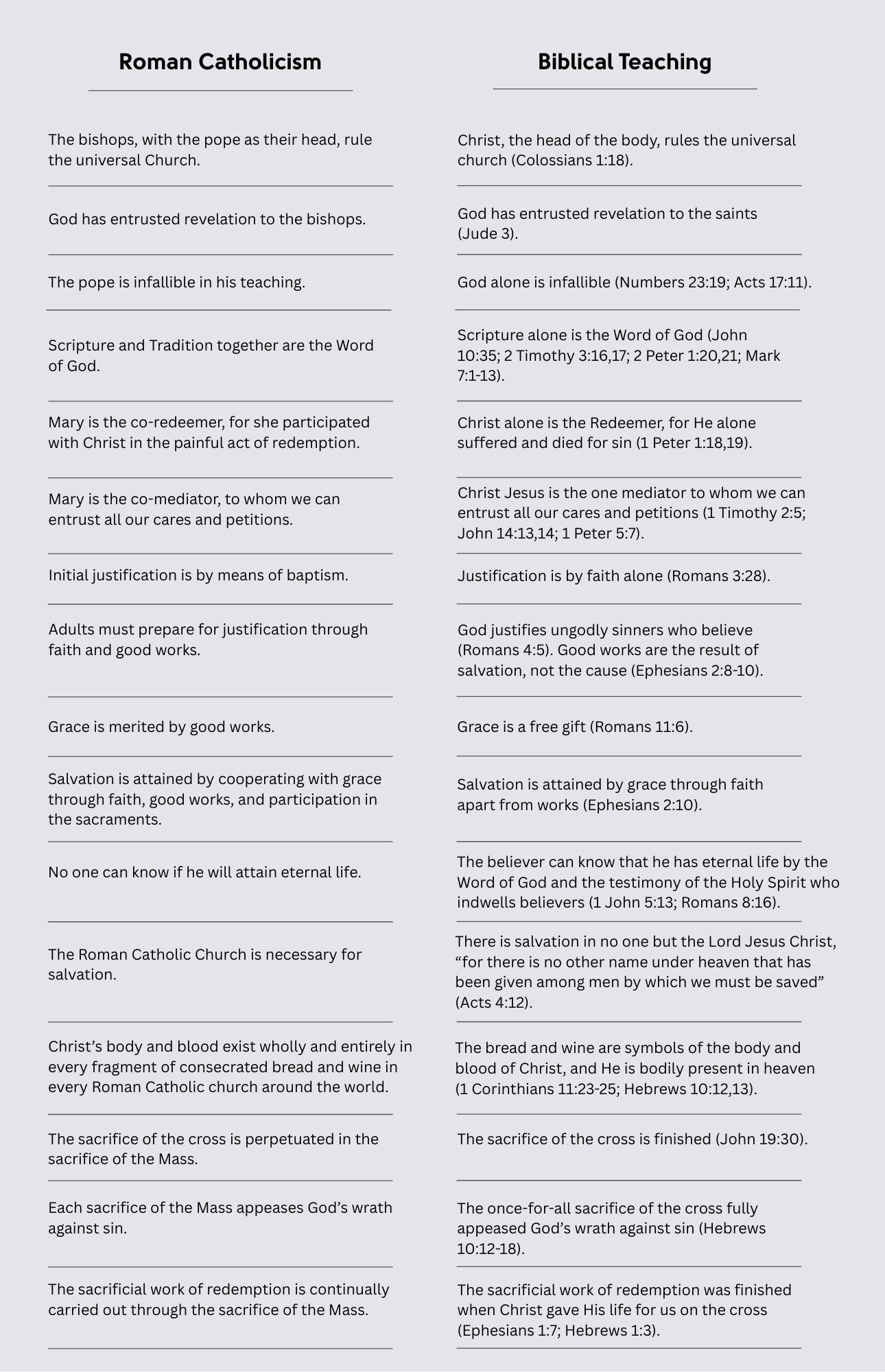

What are the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church that distinguish it from other Christian churches? Whole books have been written on this subject, but a sampling of the doctrines will be outlined here.

These doctrines don’t date back all the way to Constantine, except for perhaps in seed form, but were slowly adopted over many years as various popes issued decrees. In many cases, the doctrines are not even based on Scripture but on a document of the church. Most Roman Catholics consider themselves to be Christians and are unaware of the differences between their beliefs and the Bible. Sadly, the Roman Catholic Church has fostered that ignorance by discouraging the personal study of the Bible and making the people reliant on the priests for their understanding of the Bible.