Answer

Parts of modern-day Jerusalem have been walled in since at least the age of Abraham, when the Jebusites had their city Jebus there. In fact, some of that original wall is still visible in the southeast of the city. Seven and a half years into his reign, David conquered Jebus and adopted it as his capital (2 Samuel 5:1–10). At that time, there was at least some wall in the vicinity (2 Samuel 18:24), but Solomon was responsible for building both the temple and the wall around the city (1 Kings 3:1), fulfilling David’s prayer in Psalm 51:18. Today, the wall of Jerusalem is approximately two and a half miles long. It has an average height of almost 40 feet and an average thickness of 8 feet. The wall also contains over thirty watchtowers and eight gates.

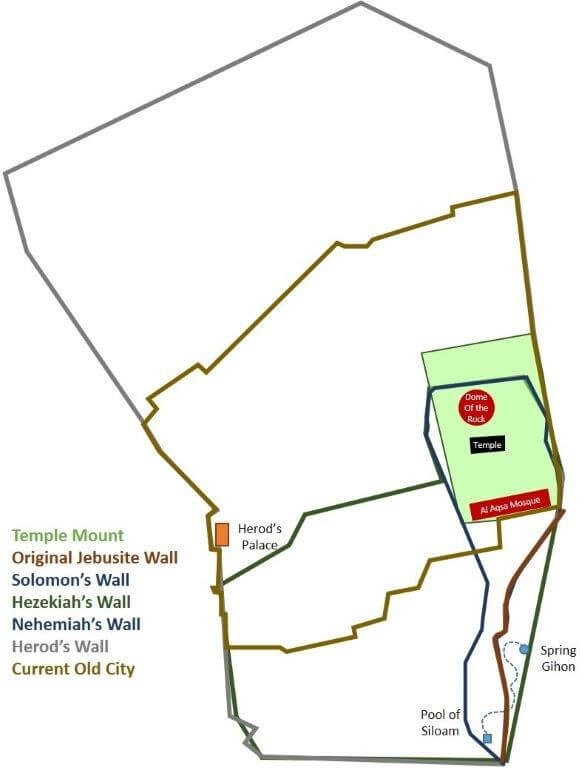

Sometime later, the good but foolish king of Judah, Amaziah, challenged the powerful king of Israel, Jehoash, to a battle (2 Kings 14). Jehoash tried to warn his challenger off, but Amaziah was resolved. Jehoash and his army trounced Amaziah, captured him, and broke down a good portion of the wall of Jerusalem in the north and northwest. Several generations later, Hezekiah became king of Judah. When Sennacherib, the king of Assyria, invaded Judah, Hezekiah had an incentive to build up the wall that Jehoash had broken as well as a larger wall around the settled area of Jerusalem southwest of the temple mount (2 Chronicles 32:5). God protected Judah and Jerusalem at that time and sent an angel to destroy Sennacherib’s army (2 Kings 19:35).

Neither the peace nor the wall of Jerusalem lasted long. King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon came through, demolished the royal court, and tore down the wall (2 Kings 25). The wall remained in its fallen state throughout the Jewish exile until Nehemiah made it his personal mission to rebuild (Nehemiah 2). Nehemiah’s wall was smaller than Hezekiah’s; under Nehemiah’s oversight, the wall reverted to the tadpole shape that encompassed the temple mount and the settlement to the south.

Around the time of Jesus, Herod the Great ruled Jerusalem and wished to leave his mark. To the south, Herod’s wall resembled Hezekiah’s. A smaller portion of the Jerusalem wall extended out to the northwest. But Herod really made alterations to the wall around the temple mount. He not only built up, he built out, outside the original, and then filled in the plateau until it was much bigger than the original—big enough for a colonnade around the sides (John 10:23; Acts 3:11; 5:12). A great ramp started at the southwest corner of the temple mount and ran in an L-shape, north and east, to an entrance on the south end of the west wall (Robinson’s Arch, a couple of rows of stones standing proud of the wall, is all that’s left). Coins that were minted after Herod’s death have been found below the footing of the wall, leading archeologists to believe Herod the Great never got to see his own legacy completed.

When Rome sacked Jerusalem in AD 70, the walls were again destroyed. It wasn’t until around the year 300 that Emperor Diocletian ordered the wall of Jerusalem restored. The Empress Eudocia, who was trained as a philosopher by her father and became a Christian when she married Emperor Theodosius II, was banished from the court and settled in Jerusalem around 450. She spent her time there writing poetry and renovating the walls. Eudocia’s walls held until shortly after the year 1000 when an earthquake took them down. Although the walls were rebuilt, they suffered greatly during the Crusades when the Christians and Muslims captured, lost, and recaptured Jerusalem. From 1535 to 1538, the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent rebuilt the walls, and they have remained to this day.